Unified Modeling Language

Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a standardized general-purpose modeling language in the field of software engineering. The standard is managed, and was created by, the Object Management Group.

UML includes a set of graphic notation techniques to create visual models of software-intensive systems.

Contents |

Overview

The Unified Modeling Language (UML) is used to specify, visualize, modify, construct and document the artifacts of an object-oriented software intensive system under development.[1] UML offers a standard way to visualize a system's architectural blueprints, including elements such as:

- actors

- business processes

- (logical) components

- activities

- programming language statements

- database schemas, and

- reusable software components.[2]

UML combines techniques from data modeling (entity relationship diagrams), business modeling (work flows), object modeling, and component modeling. It can be used with all processes, throughout the software development life cycle, and across different implementation technologies.[3] UML has synthesized the notations of the Booch method, the Object-modeling technique (OMT) and Object-oriented software engineering (OOSE) by fusing them into a single, common and widely usable modeling language. UML aims to be a standard modeling language which can model concurrent and distributed systems. UML is a de facto industry standard, and is evolving under the auspices of the Object Management Group (OMG).

UML models may be automatically transformed to other representations (e.g. Java) by means of QVT-like transformation languages, supported by the OMG. UML is extensible, offering the following mechanisms for customization: profiles and stereotype.

Unified Modeling Language topics

Software Development Methods

UML is not a development method by itself,[4] however, it was designed to be compatible with the leading object-oriented software development methods of its time (for example OMT, Booch method, Objectory). Since UML has evolved, some of these methods have been recast to take advantage of the new notations (for example OMT), and new methods have been created based on UML. The best known is IBM Rational Unified Process (RUP). There are many other UML-based methods like Abstraction Method, Dynamic Systems Development Method, and others, to achieve different objectives.

Modeling

It is very important to distinguish between the UML model and the set of diagrams of a system. A diagram is a partial graphic representation of a system's model. The model also contains documentation that drive the model elements and diagrams (such as written use cases).

UML diagrams represent two different views of a system model[5]:

- Static (or structural) view: emphasizes the static structure of the system using objects, attributes, operations and relationships. The structural view includes class diagrams and composite structure diagrams.

- Dynamic (or behavioral) view: emphasizes the dynamic behavior of the system by showing collaborations among objects and changes to the internal states of objects. This view includes sequence diagrams, activity diagrams and state machine diagrams.

UML models can be exchanged among UML tools by using the XMI interchange format.

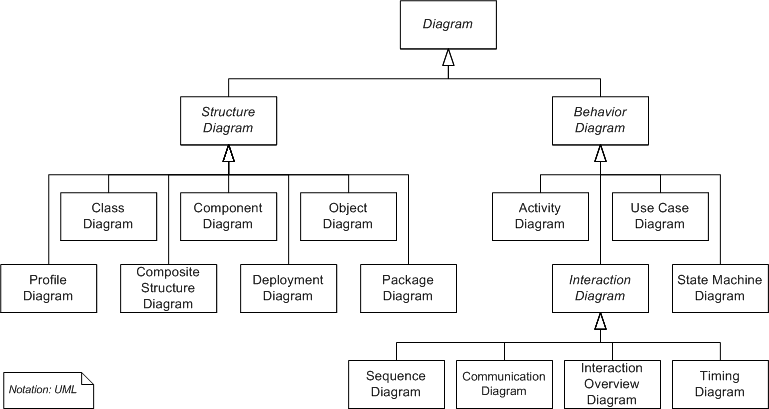

Diagrams overview

UML 2.2 has 14 types of diagrams divided into two categories.[6] Seven diagram types represent structural information, and the other seven represent general types of behavior, including four that represent different aspects of interactions. These diagrams can be categorized hierarchically as shown in the following class diagram:

UML does not restrict UML element types to a certain diagram type. In general, every UML element may appear on almost all types of diagrams; this flexibility has been partially restricted in UML 2.0. UML profiles may define additional diagram types or extend existing diagrams with additional notations.

In keeping with the tradition of engineering drawings, a comment or note explaining usage, constraint, or intent is allowed in a UML diagram.

Structure diagrams

Structure diagrams emphasize the things that must be present in the system being modeled. Since structure diagrams represent the structure they are used extensively in documenting the architecture of software systems.

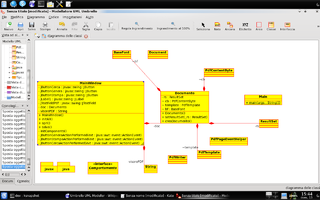

- Class diagram: describes the structure of a system by showing the system's classes, their attributes, and the relationships among the classes.

- Component diagram: describes how a software system is split up into components and shows the dependencies among these components.

- Composite structure diagram: describes the internal structure of a class and the collaborations that this structure makes possible.

- Deployment diagram: describes the hardware used in system implementations and the execution environments and artifacts deployed on the hardware.

- Object diagram: shows a complete or partial view of the structure of a modeled system at a specific time.

- Package diagram: describes how a system is split up into logical groupings by showing the dependencies among these groupings.

- Profile diagram: operates at the metamodel level to show stereotypes as classes with the <<stereotype>> stereotype, and profiles as packages with the <<profile>> stereotype. The extension relation (solid line with closed, filled arrowhead) indicates what metamodel element a given stereotype is extending.

Class diagram |

Component diagram |

Composite structure diagrams |

Deployment diagram |

|

Object diagram |

Package diagram |

Behavior diagrams

Behavior diagrams emphasize what must happen in the system being modeled. Since behavior diagrams illustrate the behavior of a system, they are used extensively to describe the functionality of software systems.

- Activity diagram: describes the business and operational step-by-step workflows of components in a system. An activity diagram shows the overall flow of control.

- UML state machine diagram: describes the states and state transitions of the system.

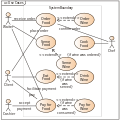

- Use case diagram: describes the functionality provided by a system in terms of actors, their goals represented as use cases, and any dependencies among those use cases.

UML Activity Diagram |

State Machine diagram |

Use case diagram |

Interaction diagrams

Interaction diagrams, a subset of behaviour diagrams, emphasize the flow of control and data among the things in the system being modeled:

- Communication diagram: shows the interactions between objects or parts in terms of sequenced messages. They represent a combination of information taken from Class, Sequence, and Use Case Diagrams describing both the static structure and dynamic behavior of a system.

- Interaction overview diagram: provides an overview in which the nodes represent interaction diagrams.

- Sequence diagram: shows how objects communicate with each other in terms of a sequence of messages. Also indicates the lifespans of objects relative to those messages.

- Timing diagrams: are a specific type of interaction diagram, where the focus is on timing constraints.

Communication diagram |

Interaction overview diagram |

Sequence diagram |

The Protocol State Machine is a sub-variant of the State Machine. It may be used to model network communication protocols.

Meta modeling

The Object Management Group (OMG) has developed a metamodeling architecture to define the Unified Modeling Language (UML), called the Meta-Object Facility (MOF). The Meta-Object Facility is a standard for model-driven engineering, designed as a four-layered architecture, as shown in the image at right. It provides a meta-meta model at the top layer, called the M3 layer. This M3-model is the language used by Meta-Object Facility to build metamodels, called M2-models. The most prominent example of a Layer 2 Meta-Object Facility model is the UML metamodel, the model that describes the UML itself. These M2-models describe elements of the M1-layer, and thus M1-models. These would be, for example, models written in UML. The last layer is the M0-layer or data layer. It is used to describe runtime instance of the system.

Beyond the M3-model, the Meta-Object Facility describes the means to create and manipulate models and metamodels by defining CORBA interfaces that describe those operations. Because of the similarities between the Meta-Object Facility M3-model and UML structure models, Meta-Object Facility metamodels are usually modeled as UML class diagrams. A supporting standard of the Meta-Object Facility is XMI, which defines an XML-based exchange format for models on the M3-, M2-, or M1-Layer.

Criticisms

Although UML is a widely recognized and used modeling standard, it is frequently criticized for the following:

- Standards bloat

- Bertrand Meyer, in a satirical essay framed as a student's request for a grade change, apparently criticized UML as of 1997 for being unrelated to object-oriented software development; a disclaimer was added later pointing out that his company nevertheless supports UML.[7] Ivar Jacobson, a co-architect of UML, said that objections to UML 2.0's size were valid enough to consider the application of intelligent agents to the problem.[8] It contains many diagrams and constructs that are redundant or infrequently used.

- Problems in learning and adopting

- The problems cited in this section make learning and adopting UML problematic, especially when required of engineers lacking the prerequisite skills.[9] In practice, people often draw diagrams with the symbols provided by their CASE tool, but without the meanings those symbols are intended to provide.

- Linguistic incoherence

- The extremely poor writing of the UML standards themselves -- assumed to be the consequence of having been written by a non-native English speaker -- seriously reduces their normative value. In this respect the standards have been widely cited, and indeed pilloried, as prime examples of unintelligible geekspeak.

- Capabilities of UML and implementation language mismatch

- As with any notational system, UML is able to represent some systems more concisely or efficiently than others. Thus a developer gravitates toward solutions that reside at the intersection of the capabilities of UML and the implementation language. This problem is particularly pronounced if the implementation language does not adhere to orthodox object-oriented doctrine, as the intersection set between UML and implementation language may be that much smaller.

- Dysfunctional interchange format

- While the XMI (XML Metadata Interchange) standard is designed to facilitate the interchange of UML models, it has been largely ineffective in the practical interchange of UML 2.x models. This interoperability ineffectiveness is attributable to two reasons. Firstly, XMI 2.x is large and complex in its own right, since it purports to address a technical problem more ambitious than exchanging UML 2.x models. In particular, it attempts to provide a mechanism for facilitating the exchange of any arbitrary modeling language defined by the OMG's Meta-Object Facility (MOF). Secondly, the UML 2.x Diagram Interchange specification lacks sufficient detail to facilitate reliable interchange of UML 2.x notations between modeling tools. Since UML is a visual modeling language, this shortcoming is substantial for modelers who don't want to redraw their diagrams.[10]

Modeling experts have written sharp criticisms of UML, including Bertrand Meyer's "UML: The Positive Spin",[7] and Brian Henderson-Sellers and Cesar Gonzalez-Perez in "Uses and Abuses of the Stereotype Mechanism in UML 1.x and 2.0".[11]

History

Before UML 1.x

After Rational Software Corporation hired James Rumbaugh from General Electric in 1994, the company became the source for the two most popular object-oriented modeling approaches of the day: Rumbaugh's Object-modeling technique (OMT), which was better for object-oriented analysis (OOA), and Grady Booch's Booch method, which was better for object-oriented design (OOD). They were soon assisted in their efforts by Ivar Jacobson, the creator of the object-oriented software engineering (OOSE) method. Jacobson joined Rational in 1995, after his company, Objectory AB[12], was acquired by Rational. The three methodologists were collectively referred to as the Three Amigos, since they were well known to argue frequently with each other regarding methodological practices.

In 1996 Rational concluded that the abundance of modeling languages was slowing the adoption of object technology, so repositioning the work on a unified method, they tasked the Three Amigos with the development of a non-proprietary Unified Modeling Language. Representatives of competing object technology companies were consulted during OOPSLA '96; they chose boxes for representing classes over Grady Booch's Booch method's notation that used cloud symbols.

Under the technical leadership of the Three Amigos, an international consortium called the UML Partners was organized in 1996 to complete the Unified Modeling Language (UML) specification, and propose it as a response to the OMG RFP. The UML Partners' UML 1.0 specification draft was proposed to the OMG in January 1997. During the same month the UML Partners formed a Semantics Task Force, chaired by Cris Kobryn and administered by Ed Eykholt, to finalize the semantics of the specification and integrate it with other standardization efforts. The result of this work, UML 1.1, was submitted to the OMG in August 1997 and adopted by the OMG in November 1997.[13]

UML 1.x

As a modeling notation, the influence of the OMT notation dominates (e. g., using rectangles for classes and objects). Though the Booch "cloud" notation was dropped, the Booch capability to specify lower-level design detail was embraced. The use case notation from Objectory and the component notation from Booch were integrated with the rest of the notation, but the semantic integration was relatively weak in UML 1.1, and was not really fixed until the UML 2.0 major revision.

Concepts from many other OO methods were also loosely integrated with UML with the intent that UML would support all OO methods. Many others also contributed, with their approaches flavouring the many models of the day, including: Tony Wasserman and Peter Pircher with the "Object-Oriented Structured Design (OOSD)" notation (not a method), Ray Buhr's "Systems Design with Ada", Archie Bowen's use case and timing analysis, Paul Ward's data analysis and David Harel's "Statecharts"; as the group tried to ensure broad coverage in the real-time systems domain. As a result, UML is useful in a variety of engineering problems, from single process, single user applications to concurrent, distributed systems, making UML rich but also large.

The Unified Modeling Language is an international standard:

- ISO/IEC 19501:2005 Information technology — Open Distributed Processing — Unified Modeling Language (UML) Version 1.4.2

UML 2.x

UML has matured significantly since UML 1.1. Several minor revisions (UML 1.3, 1.4, and 1.5) fixed shortcomings and bugs with the first version of UML, followed by the UML 2.0 major revision that was adopted by the OMG in 2005[14].

Although UML 2.1 was never released as a formal specification, versions 2.1.1 and 2.1.2 appeared in 2007, followed by UML 2.2 in February 2009. UML 2.3 was formally released in May 2010[15].

There are four parts to the UML 2.x specification:

- The Superstructure that defines the notation and semantics for diagrams and their model elements;

- the Infrastructure that defines the core metamodel on which the Superstructure is based;

- the Object Constraint Language (OCL) for defining rules for model elements;

- and the UML Diagram Interchange that defines how UML 2 diagram layouts are exchanged.

The current versions of these standards follow: UML Superstructure version 2.3, UML Infrastructure version 2.3, OCL version 2.2, and UML Diagram Interchange version 1.0[16].

Although many UML tools support some of the new features of UML 2.x, the OMG provides no test suite to objectively test compliance with its specifications.

See also

- Glossary of Unified Modeling Language terms

- Agile Modeling

- Entity-relationship model

- Executable UML

- Fundamental modeling concepts

- List of UML tools

- Meta-modeling

- Model-based testing

- Model-driven integration

- Software blueprint

- SysML

- UML state machines

- UML colors

- UML eXchange Format

- UN/CEFACT's Modeling Methodology

- Message Sequence Chart, another type of Interaction diagrams

- Object Process Methodology, an alternative "... to designing information systems by depicting them using object models and process models". And, presenting these in one unified view.

References

This article was originally based on material from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing, which is licensed under the GFDL.

- ↑ FOLDOC (2001). Unified Modeling Language last updated 2002-01-03. Accessed 6 feb 2009.

- ↑ Grady Booch, Ivar Jacobson & Jim Rumbaugh (2000) OMG Unified Modeling Language Specification, Version 1.3 First Edition: March 2000. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ↑ Satish Mishra (1997). "Visual Modeling & Unified Modeling Language (UML) : Introduction to UML". Rational Software Corporation. Accessed 9 Nov 2008.

- ↑ John Hunt (2000). The Unified Process for Practitioners: Object-oriented Design, UML and Java. Springer, 2000. ISBN 1852332751. p.5.door

- ↑ Jon Holt Institution of Electrical Engineers (2004). UML for Systems Engineering: Watching the Wheels IET, 2004 ISBN 0863413544. p.58

- ↑ UML Superstructure Specification Version 2.2. OMG, February 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bertrand Meyer. "UML: The Positive Spin". http://archive.eiffel.com/doc/manuals/technology/bmarticles/uml/page.html. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ "Ivar Jacobson on UML, MDA, and the future of methodologies" [1] (video of interview, transcript available), Oct 24, 2006. Retrieved 2009-05-22

- ↑ See the ACM article "Death by UML Fever" for an amusing account of such issues.

- ↑ UML Forum. "UML FAQ". http://www.uml-forum.com/FAQ.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ B. Henderson-Sellers; C. Gonzalez-Perez (2006). "Uses and Abuses of the Stereotype Mechanism in UML 1.x and 2.0". in: Model Driven Engineering Languages and Systems. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg.

- ↑ Objectory AB, known as Objectory System, was founded in 1987 by Ivar Jacobson. In 1991, It was acquired and became a subsidiary of Ericsson.

- ↑ UML Specification version 1.1 (OMG document ad/97-08-11)

- ↑ http://www.omg.org/spec/UML/2.0/

- ↑ http://www.omg.org/spec/UML/

- ↑ OMG. "Catalog of OMG Modeling and Metadata Specifications". http://www.omg.org/technology/documents/modeling_spec_catalog.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

Further reading

- Ambler, Scott William (2004). The Object Primer: Agile Model Driven Development with UML 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54018-6. http://www.ambysoft.com/books/theObjectPrimer.html.

- Chonoles, Michael Jesse; James A. Schardt (2003). UML 2 for Dummies. Wiley Publishing. ISBN 0-7645-2614-6.

- Fowler, Martin. UML Distilled: A Brief Guide to the Standard Object Modeling Language (3rd ed. ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-19368-7.

- Jacobson, Ivar; Grady Booch; James Rumbaugh (1998). The Unified Software Development Process. Addison Wesley Longman. ISBN 0-201-57169-2.

- Martin, Robert Cecil (2003). UML for Java Programmers. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-142848-9.

- Noran, Ovidiu S.. "Business Modelling: UML vs. IDEF" (PDF). http://www.cit.gu.edu.au/~noran/Docs/UMLvsIDEF.pdf. Retrieved 2005-12-28.

- Penker, Magnus; Hans-Erik Eriksson (2000). Business Modeling with UML. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-29551-5.

External links

- UML Resource Page of the Object Management Group – Resources that include the latest version of the UML specification from the group in charge of define the UML specification

- Death by UML Fever – An ACM queue article about the abuse of UML

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||